Home Is Home, Backwater Veteran Says

By Jared Poland

Anderson Jones Sr. has lived all his life at the base of the levee system designed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to protect the Lower Mississippi Delta from high levels on the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers.

Jared Poland

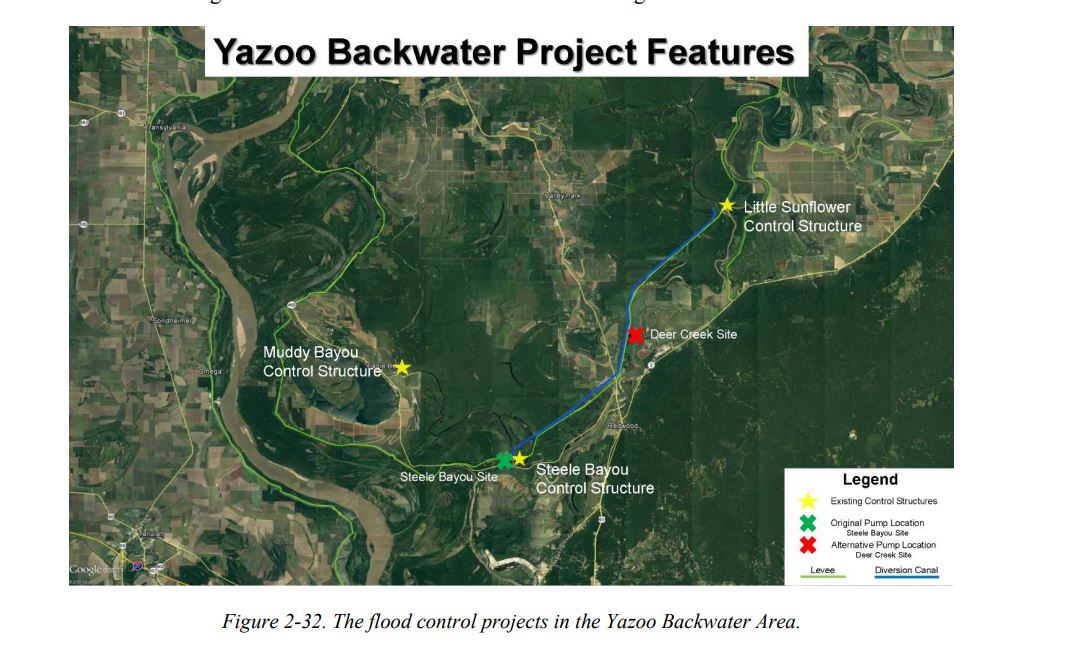

The levees have a drain plug. When the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers are below flood levels, rain falling on most of the northwest quadrant of Mississippi makes its way through that plug and into the river system. When the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers are high, gates of that drain plug – the Steele Bayou Control Structure – are closed to keep river water from backing up onto the flat and fertile expanse that is the Mississippi Delta. But while keeping river water out, the closure of the control structure prevents rain runoff from draining. It “ponds” inside the levees – sometimes a little, and sometimes a lot.

Any bit of rainfall after the structure is closed begins to accumulate in the backwater area with no place to go. If there is little rainfall in the area there is little backwater flooding, but when precipitation is heavy, water can quickly accumulate causing catastrophic conditions.

Spring rain levels are unpredictable, and the backwater can rise very quickly, especially where Jones has lived all his life. “It’s always in the back of my mind,” he said. “When it gets to raining, I say, ‘Lord, please let it stop, just let it stop.‘” In the first six months of 2019, precipitation in the Delta exceeded averages by only about 10 inches, but a little rain floods vast areas when it can’t be drained.

Jones‘ modest home where he and his wife live has an address in Filter, Mississippi, an unincorporated town. It is in Issaquena County, which similarly has fewer than 2,000 residents — the smallest population in the state. What the county lacks in people, it redoubles in farmland used to grow corn, cotton and soybeans in furrowed fields stretching to the horizons.

His home might not be much to anyone else, he said, but to him it has served as the central point for his life. It is where the couple raised their two children and he still pursues his passion of training dogs. Communicating with the pups is a gift, he said. Not many have it. Two yapping dogs show their affection for their friend.

Jones has lived on his property since he was a small child. When he was young, he planted a seed with his mother in their front yard. That seed is now a large tree that has grown to drape over the gravel road out front. He knows he could move, but his fondness for his property is visceral. “There is no place like home,” he said.

Designing the levee system was assigned to the Corps by Congress in the aftermath of 1927 flooding, which, until recent years, was the worst ever on the Lower Mississippi. The plan eventually included pumps at the Steele Bayou Control Structure that would lift the impounded rainwater over the levee and into the river system. For decades, actual construction of a pumping array has been an on-again, off-again proposition. Jones has been a consistent advocate. He has a soft voice, but has testified before Congress in Washington, D.C., and has spoken with U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson, who represents the Delta in the House. He’s given countless interviews, taken dozens of media representatives on tours.

For much of 2019, Jones, who moves slowly due to a brace on his leg, worked to defend his home from encroaching water. It wasn’t a record year for river flooding, but the backwater rose and rose, and eventually Jones had to boat from a slightly higher road to his house to keep working on the sandbag levee he built around it, and fight off snakes with his shotgun.

Jared Poland

Despite his efforts, late one evening in 2019, Jones and his son, Anderson Jones Jr., had to evacuate the home as water began rushing in. They got out safely, but the home was effectively destroyed.

“That water was in here 150 days,” he said while walking through his home. The extended flooding allowed for inches of mud, streaks and pockets of mold and mildew spreading all the way into the attic to ravish the property.

After the water receded, Jones, with the help of neighbors and family, began working at a steady pace to restore his home to a habitable level. He had insurance, but it was nowhere close to covering the full cost of repairs. Jones and his wife lived with different family members in Jackson and Vicksburg. For almost a year, tedious work progressed on removing flooring and walls, tearing out molded ceilings, rebuilding doorways, painting and everything else. The nearest building supply store is in Rolling Fork, almost an hour away.

Many people suggested that he just move as they have after every flood year, but Jones was determined to stay where his heart and memories reside.

While 2019 was the longest and most damaging period of flooding he had experienced, it was not the deepest flood that he has seen in his lifetime. That was in 1973 when water filled his home to almost chest height. During that year he and his siblings would wade or boat a half-mile through stagnant water that covered their road to meet the school bus. His said his siblings often would try to skip school saying they were sick because they did not want to show up muddy as they often did after their morning trek through the swamp to school.

Jones remembered his father having to hold his sister, a polio patient, in the boat because she was unable to sit due to a cast on her leg. A reminder of that year can be found on a wall stud in the back corner of his home where a dark stain clearly marks how high the water was in 1973. Every time the control structure closes, Jones said he is reminded of the danger.

“You don’t know when it’s going to flood,” he said. “When they close those gates, you’re in trouble.”