Facts

By Jared Poland

Starting in the early 1820s, Congress recognized the importance of the Mississippi River and its tributaries as major arteries of commerce and prosperity and tasked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to plan and carry out projects to maintain navigation.

A century later following devastating Mississippi River flooding in 1927 and two other severe floods in 1934 and 1935, Congress passed the Federal Flood Control Act of 1936. The act recognized that piecemeal work done by states and localities just wasn’t enough, and again turned to Army engineers to develop comprehensive plans and to manage flood controls along waterways of the United States.

For the particularly troublesome challenge of the vast, flat Mississippi Delta, Congress commissioned the Yazoo Basin, Yazoo Backwater Project on Aug. 18, 1941. Now, 80 years later, one unconstructed component of the comprehensive plan has, in the wake of unprecedented 2019 flooding, come to the fore again. “Finish The Pumps” is the battle cry of almost all landowners and residents of the region. As they have for decades, environmental groups oppose the pumps and insist they’d do more harm than good.

Topography is key in the situation. The Mississippi Delta, some of the most fertile land in the nation, covers most of the northwest quadrant of the state. There is very little elevation change between Vicksburg, at the base of the Delta, and Memphis, Tenn.

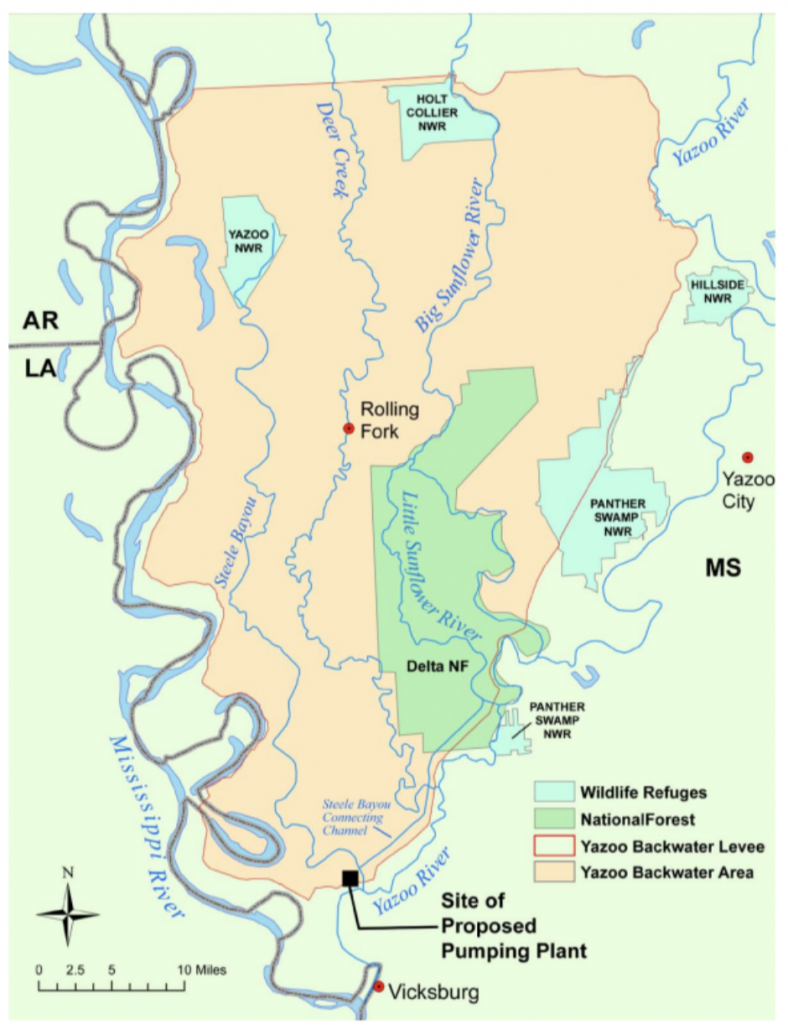

The Mississippi River forms the western border of both the state and the Delta, and is contained by a sturdy mainline levee. During floods, that levee keeps river water off the cropland. The Yazoo River angles northeast from Vicksburg where it empties into the Mississippi, forming a rough “V.“ The 922,000 acres of forest and cropland, known as the Yazoo Backwater Area, are in the center of the “V” and levees along the Yazoo have been constructed to keep river water from making an end run, in essence, and flooding the Delta from the East.

Steele Bayou extends more or less through the center of the Delta and, in normal times, drains rain water from 4,039 square miles of land to the base of the “V” and through a gated control structure into the Yazoo River.

It takes a combination of events for the Yazoo Backwater to flood. First, the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers have to rise enough to cause the Corps to close the gates in order to keep river water from backing into the Delta. Second, there has to be heavy rain in the Delta at the same time. With the gates closed, that rainwater is trapped or impounded with no place to go. It spreads out, inundating field after field.

Overall, the Yazoo Backwater project design includes plans for levees, gravity control structures, and pumps to reduce flood risk from the Mississippi River. Only the pumps — that would lift the impounded rainwater over the levee and into the river system — have not been constructed.

The absence of pumps is not a problem every year. For example, there were only minor problems in 2020. But the unprecedented Delta flooding in 2019 is seen as foreshadowing more years when farmers can’t farm, workers can’t work, wildlife drowns or starves and Mississippi’s agribusiness and tourism economy takes a hit worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Mississippi, of course, was not the only place sustaining vast flood damage. Vast regions of Nebraska and other heartland states were inundated for much of the year. A pattern has been noted.

“In terms of climate change, research has shown that the snow is melting earlier which means the snowpack just melts faster,” said Jamie Dyer a professor of meteorology and climatology at Mississippi State University.

That has added impetus for a push for Congress to revisit the problem.

As designed and, now, redesigned, the primary component of the project is a 14,000 cubic-feet-per-second pumping station, near the Steele Bayou flood control gates, to move rainwater out of the Yazoo Backwater Area during high water events on the Mississippi River.

Debated and litigated for decades over issues of cost, cost-sharing, cost-benefit ratio, environmental matters in more, the plan for pumps was last deemed dead on Feb. 1, 2008, when the federal Environmental Protection Agency used its Clean Water Act authority to veto construction.

The act allows the EPA to halt specification of any defined area as a disposal site, or restrict or deny the use of any defined area for specification as a disposal site for the discharge of dredged or fill material. Actions have mostly been taken in response to unresolved Corps permit applications, and vetoes are rare. The Corps authorizes about 68,000 permits each year. In contrast, the EPA has used its Section 404 (c) power in only 13 final determinations since 1972.

In every proposal developed, including a new draft that has a hint of life in Congress, the construction and operation of pumps would reduce the extent, depth, frequency, and duration of flooding. No plan would drain all the wetlands in the Delta, which are the natural asset environmentalists insist must be protected.

According to the Corps, the Yazoo Backwater Area contains 150,000 to 229,000 acres of wetlands. It also features an extensive network of streams, creeks and other aquatic resources. Wetlands provide habitat and also provide important ecological functions, protect and improve water quality by removing and retaining pollutants, temporarily storing surface water, maintaining stream flows, and supporting aquatic food webs by processing and exporting significant amounts of organic carbon.

The Delta wetlands are some of the richest resources in the nation, and the EPA and environmentalists opposed to the pumps because they believed it would degrade or eliminate 67,000 acres, causing unacceptable adverse impacts on wildlife and fisheries resources. A proposed mitigation plan was also believed to not adequately compensate for the project’s impact.

The wetlands and forests are also an asset to landowners who manage or lease rights to hunt, particularly ducks, and fish. Environmental tourism is a growth industry, and one company, Tara Wildlife, has set a standard for excellence in the area for the tens of thousands of acres it owns and operates as either a preserve or an area for hunting. Tara and other individuals and groups provided tons of supplemental food for wildlife in 2019 in an effort to fight starvation.

The EPA, which has said its 2008 veto does not apply to the revised and updated plan for pumps now on the table, points out that the projected additional wetland loss must be viewed in the context of the cumulative losses all across the Lower Mississippi River Alluvial Valley, which has already lost over 80 percent of its bottomland forested wetlands to clearing for agriculture. Specifically in the Mississippi Delta, the EPA says the project would significantly degrade important bottomland forested wetlands.

Those realities stand against the nine of the past 10 years when the Yazoo Backwater Area has experienced flooding to some extent. According to the Mississippi State University Delta Research and Extension center, the 2019 flooding damaged 680 homes, caused two deaths, large levels of ecological damage and animal deaths along with other issues related to floodwater covering so much of the area for so long.

Flooding has long plagued the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, but the due to a perceived lack of media attention, the so-called “forgotten” floods of 2019 were quite possibly the worst ever. Now, many who have been indifferent to the pumps debate understand the threat that flooding has to their homes and livelihoods. Many of those community members are fighting back against the EPA and environmentalists and lobbying to finishing the pumps. Large, homemade signs and even billboard reading “Finish the Pumps” can be seen on along U.S. 61 near Rolling Fork.

In the political arena, Gov. Tate Reeves and U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith are advocates for the pumps. In a press conference in September 2020, Reeves, Hyde-Smith and estimated the value of crops not grown to be at least $800 million. The state also spent over $1 million to clean up bridges and roads. In wildlife management areas there was an estimated loss of $310,000 in revenue.

At Mississippi State University, Dyer studies, models and predicts extreme hydrologic events. He also has recently been using drones to image and assess flood conditions along the Mississippi. When there is more snow and it melts rapidly in the north and drains into the Mississippi it causes the normal spring rise to flow much faster and rise much more sharply.

There are other facets to the challenge. When the drainage structure‘s gates are closed, and rain falls and accumulates in the Delta, this stagnant water can become rife with agricultural run-off containing chemicals such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

As temperatures rise when the summer months near, plant life begins to explode, catalyzed by the agricultural chemicals in the water. “The higher the temperature the faster the plants grow,” Dyer said.

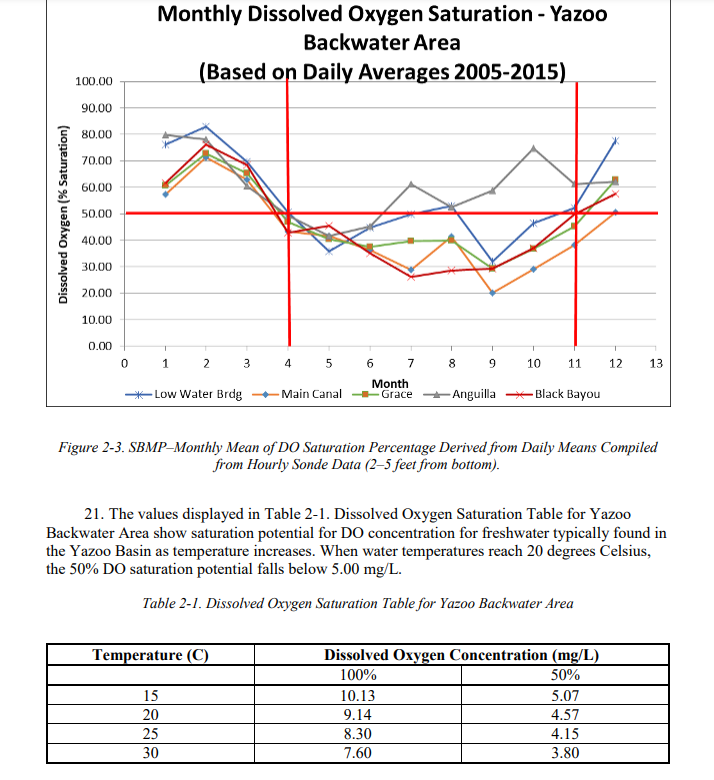

As plants grow, the water quickly becomes void of oxygen. This deoxygenation is caused by biological processes using the oxygen. The water is not able to move, mix and subsequently reoxygenate. The stagnation and agricultural run-off that fuel these hypoxic conditions that can last for months and often decimate aquatic habitats.

“If you let it sit there and it becomes hypoxic, your pumping for all intents and purposes dead water into the river,” Dyer said. When the gates were finally opened, the lifeless hypoxic water drained south into the Gulf of Mexico. This water was hotter and more hypoxic then if it had been pumped out earlier in the year.

“If they are pumping it out basically what they are doing is allowing that water to move,” Dyer said. According to the Corps, if the water is pumped out earlier, when it is cooler and at lower hypoxic levels, it will likely improve the dissolved oxygen levels and diminish the negative impacts on aquatic life in the area. Without the pumps, hypoxic conditions will likely appear again the next time the area experiences extended flooding.

On the other hand, pumping the water out maintains a more or less natural flow. “The closer you are to a natural environment the better,” Dyer said.

Despite efforts to tame the Mississippi, the river is constantly changing and becoming more unpredictable by the year. “These structures were built based on average conditions in the ’60s and ’70s and we are not at those conditions anymore,” Dyer said. “We’re going to have stronger floods, and we are going to have stronger droughts,” Dyer said.

The flood of 2019 was catastrophic, but climatologists fear that a more catastrophic event could occur in the future.

In a worst-case, if there were massive amounts of snow in the winter, followed by a warm spring that rapidly melts snow as in in 2019, combined with frequent and severe hurricanes coming from the Gulf as in 2020, it would likely be much more destructive.

“That would basically destroy every river system down the channel,” Dyer said. “We hope that doesn’t happen, but it could happen, and that potential increases every year.”

2019 Flooding Data

- 550,000 acres or about 860 square miles flooded for up to 150 days.

- That’s 1.5 times the size of Los Angeles metro area and 38 times the area of Manhattan.

- Land cleared for crops accounted for 230,000 acres of the total.

- Only a few inches of flooding makes cropland unusable.

- 680 homes damaged or destroyed.

- Uncounted thousands of whitetail deer, turkeys and other wildlife drowned or starved.

Key results of ‘Forgotten Flood’

- $42,160 per affected household in self-assessed costs to deal with the flood not expected to be covered by insurance or assistance programs.

- $3,217 per resident in average additional commuting distance and time.

- $5,183 per worker on average missed days and hours of work.

- 69 percent of workers report a reduction in work productivity as result of stress and fatigue associated with the flood.

-Mississippi State Extension Service