Facts

By Eliza Noe

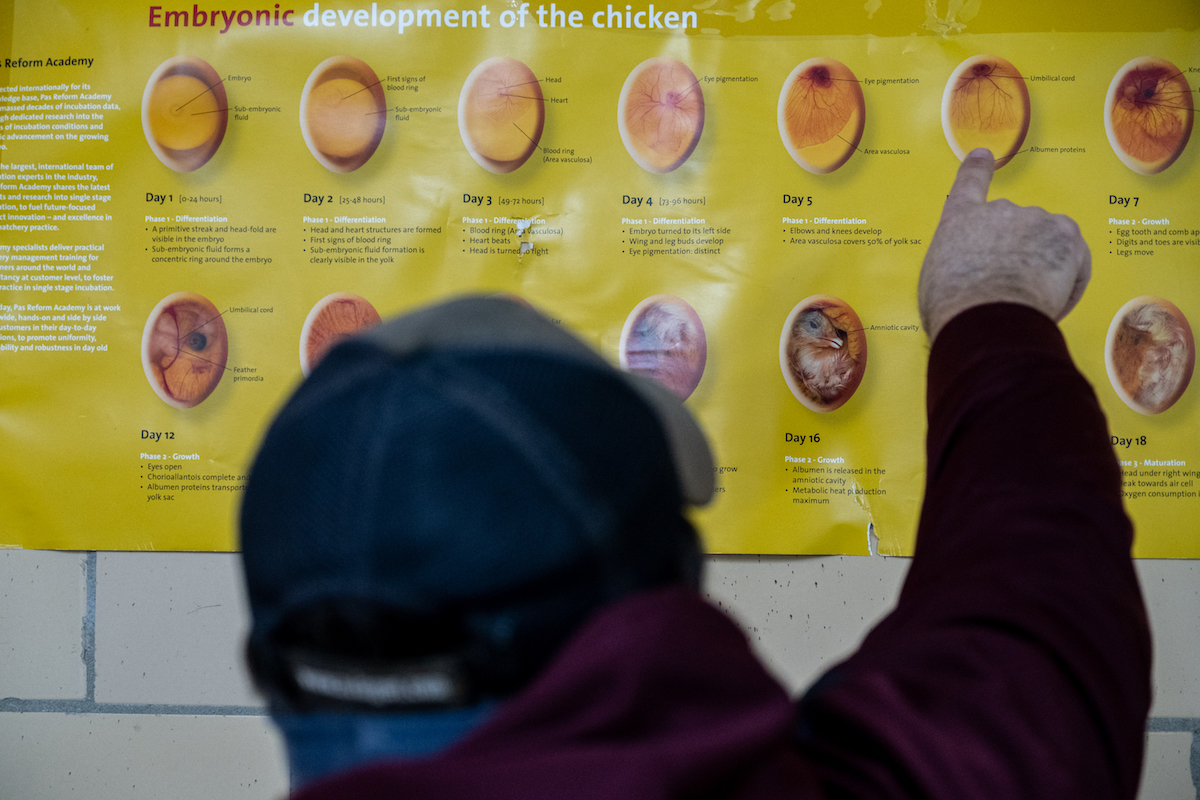

When speaking about how important the chicken industry has been in his 40-year career, Mississippi State University poultry science Professor Tom Tabler said it simply: “Chickens pay the bills.”

For the entire state, it’s much the same. Mississippi ranks 5th among the 50 states in broiler chicken production, with 1,237 farms producing 756 million broilers annually and bringing more than $2 billion to the state economy.

However, higher temperatures and larger chickens are leading to higher production costs for growers, and the growers are using science and technology to remain competitive.

Many may not realize it, but due to genetic modifications the size of commercial chickens has quadrupled since 1957. Chickens are warm-blooded animals, so, of course, larger chickens are also giving off more heat, and that makes it much more difficult to prevent heat stress.

Broilers, which are chickens specifically grown for consumption, account for approximately 94 percent of the total poultry industry sales. Meanwhile, eggs account for about 5 percent, which is still $155 million annually. Hens account for 1 percent and noncommercial farm chickens account for less than 1 percent.

Egg Production

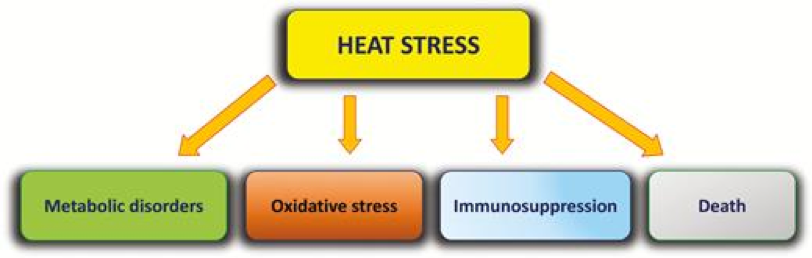

Inevitable rising temperatures pose a drastic negative threat to laying hens, those farmed to produce eggs. According to a study published by Hasanuddin University in Indonesia, how heat affects chickens’ bodies can disrupt the entire chain of production, which could cause higher prices at restaurants and in grocery stores.

Billy Schuerman

“Decreased feed intake is the most harmful effect of heat stress at the beginning of laying hens production, which leads to a decrease in body weight, feed efficiency, production and quality of eggs,” the study said. “However, in addition to the reduction in feed intake, the impact of heat stress also leads to a decrease in feed digestibility, and decreased plasma protein and calcium levels.”

In sum, If chickens are not taking on weight or digesting correctly, overall production of eggs and the quality of the eggs decreases. According to the study, the longer a chicken is overheated and the higher the temperature rises, the more damaged are the eggs.

“When the temperature rose from 86 degrees to 100 degrees, the hens will produce eggs with a thin egg shell due to a decline in calcium and bicarbonate in the blood of a chicken,” the study said. “At a temperature of 105 degrees there was higher risk of death, whereas at a temperature of 116 degrees had caused the death.”

As to quantity is also an issue, Tabler said, “Chickens don’t have to lay eggs, so eggs are kind of a gift,” he said. “If a chicken is under a lot of stress, it’s going to quit laying eggs, or it might not lay an egg every day. Then it might be two or three more days before it lays an egg again, because (the chicken’s body) is going to take care of its own needs first.”

Fighting Stress

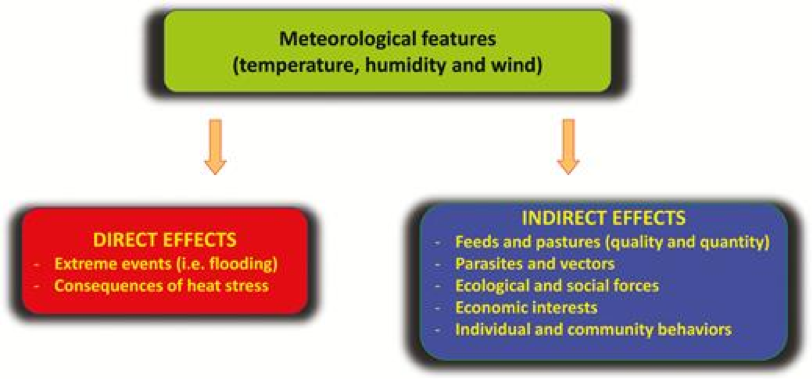

The heat forecast? According to the Environmental Protection Agency, 70 years from now, Mississippi is likely to have 30 to 60 days per year with temperatures above 95 degrees, compared with about 15 days today. To date? Summers in Mississippi usually range between 89 and 92 degrees, but in July 2020, temperatures rose to 107 degrees on its hottest days.

Yearly, it is estimated the poultry industry loses $128 to $165 million nationally due to heat stress in broilers.

Mississippi growers have long used different devices and methods to help ease the stress that chickens have during the summers. Growers who have large-scale layer houses have installed ventilation systems in their facilities. Traditionally, ventilation was mainly for preventing moisture in the houses during winter months, which makes the birds vulnerable to disease. According to research by Tabler and Jessica Wells, a colleague at Mississippi State, selecting fans for chicken houses is now crucial to the survival of chicken and is part of the “ventilation puzzle.”

Billy Schuerman

The cool cell is used to maintain a consistent temperture in the broiling house. This is where chickens are grown at the Mississippi State Poultry Science labs.

“Fan management is critical to keeping birds alive in hot weather; however, it is also important in winter to prevent over-ventilating,” they wrote. “Over-ventilating can needlessly exhaust heat and increase the gas bill (for heating); therefore, when building a new house or retrofitting an older one, selecting the proper fan is the most important decision a grower makes.”

Fans are generally located at the ends of metal-roofed chicken houses, often 600 feet long. On one end the fans are cool cells with wet ventilation pads through which the fans pull hot air from outside to create cooler air inside. This creates an air-conditioned effect for the chickens.

“Those fans are running constantly in hot weather, July and August,” he said. “With big chicken houses those fans are running 24 hours a day. They never shut off. There’s always airflow going through that house.”

Good ventilation, though, comes at a price. The website globalindustrial.com lists agricultural fans anywhere from $500-$2,000 each, and larger commercial chicken houses can have anywhere between 12 and 16 fans. Tabler and Wells argue that the investment is worth it.

“It may take two to three years to see the payback from reduced electrical consumption, but a high-quality fan continues to save you money long after that.”

Billy Schuerman

The panel is used to regulate the temperture in the broiling house automatically. “The panel is a tremendous help but it doesn’t replace the fact that you need to be here to check your chickens everyday,” Dr. Thomas Tabler said.

Tabler added that measures taken in years past are not enough to keep today’s chickens alive. “A 400 feet-per-minute air speed down the house that used to be fine just a few years ago is no longer enough,” he said. “Modern, tunnel-ventilated broiler houses often reach 600-700 feet per minute with some new houses capable of 900-1,000 feet per minute, and every bit of it is needed.”

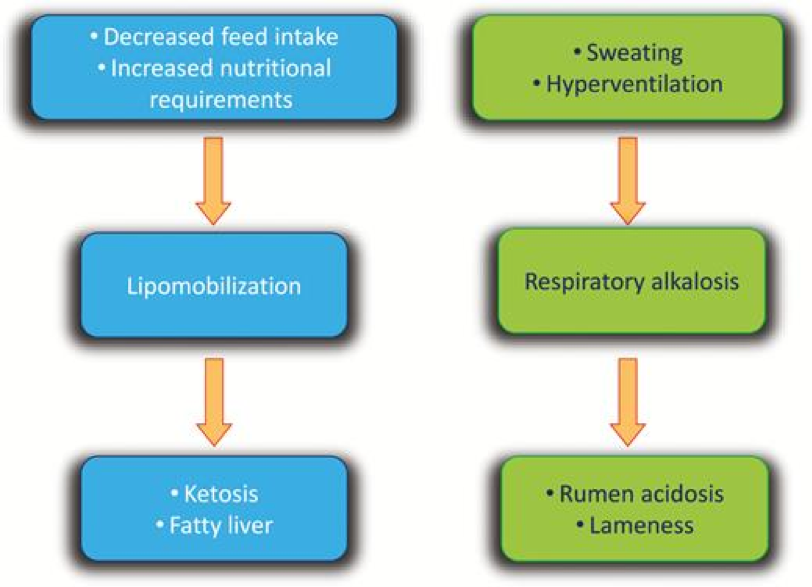

In addition to ventilation, sprinkler systems have been instrumental in keeping chickens alive in summer months. According to Tabler, high humidity — not just high temperatures — are what cause deaths among the birds. Unlike humans, chickens cannot sweat.

“In the early 1980s, before the advent of cool cells and when I was a broiler service tech in Arkansas, I saw many summer days when the house temperature was 90 degrees or higher but humidity was below 50 percent,” Tabler said. “No birds died from the heat.”

Since chickens have to release heat and moisture through breathing, higher humidity means less air to use to take up heat and moisture. For example, when the air is 50 percent humidity, there’s still 50 percent left to expel heat. However, when humidity is at 90 percent, that only leaves chickens with 10 percent of remaining humidity to cool down.

“I also saw days when house temperatures were in the low-to-mid 80s but humidity was 80 percent or higher,” Tabler said. “Chickens died by the thousands from heat prostration. This was often after summer thunderstorms moved through around 3 p.m. The sun was back out by 4 p.m., and folks were picking up dead birds by 6 p.m.”

According to the National Climatic Data Center, Mississippi has, on average, the highest humidity levels in the country at 91 percent. That number can climb to 93 percent during the summer.

“When the weather gets hot, a chicken can stand a fair amount of high temperature if the humidity level is not really high,” Tabler said. “Unfortunately, here in Mississippi, the humidity level is pretty much high all the time, which complicates the situation for chickens grown in hot weather.”

Many consumers prefer more humane ways of raising the chickens they purchase, so many are specifically shopping for pasture-raised or free-range birds. This comes at a cost, however, since raising chickens in pastures means less control over the environmental conditions.

In addition to higher temperatures, heavier wet seasons and drier dry seasons are going to take a toll on the health of pasture chickens. If too wet, the chickens can be in a constant state of hypothermia (losing body heat), and in drought conditions, there are fewer insects, which means less food.

Jeff Mattocks, who works for an organic feed company, told Yale Climate Connections that droughts pose a great risk as the chickens are not given the cooling opportunities that housed chickens have.

“There’s nothing green out there,” he said. “So if you’ve ever laid down in green grass and felt how cool it makes you feel, in a drought year, we don’t have that.”

Tabler echoed Mattocks’s statements. Temperature-wise, he said, the chickens are safer in the houses. “We moved chickens inside for a reason, he said. “Because of the things that are after them are outside: the critters are outside (and) the diseases are outside. Bad weather is outside; (there are) 100-degree temperatures in the summertime, 20-degree temperatures in the wintertime. Conditions in that chicken house or temperature wise are basically as close to ideal for those chickens as what they can be.”

Planning Ahead

Though it’s hard to predict what the industry will look like one or two decades down the line, Tabler is confident that there will still need to be adaptations in order to keep the birds alive in the summers. His proposal: focus on water conservation.

“Summers are going to be hotter, and that’s going to make you know the chicken folks have to worry more early,” he said. “Because the hot weather is going to arrive sooner than it used to, and it’s going to hang on longer than what it used to. There’s going to have to be methods that take advantage of using less water, but do the same thing to get the same result.”

Billy Schuerman

Poultry Science students at Mississippi State University grow up to 400-500 chickens in the student broiling house over the couse of a semester.

In Canada, engineers are perfecting recycling sprinkler devices. Tabler said that the finished product could save between 35-40 percent of the water that a cool cell uses. However, the devices require a higher temperature within the house, which Tabler said scares chicken farmers from testing them. Many farmers also use well-water instead of city water to furnish their houses. This, according to Tabler, is not sustainable.

“If you’ve got six houses on your farm, you’re trying to run cool-cell water through all six of those,” he said. “Those chickens are drinking a lot of water because they’re big, (and) it puts a big demand on that underground aquifer. You may or may not have enough water five years down the road from now — 10 years down the road from now— to continue to grow chickens.”

In the end, Tabler said, farmers will continue to adapt as best they can and try to keep up with warming environments and genetic modifications. “Farming is seven days a week, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The chickens don’t care whether it’s your birthday, your anniversary, Christmas, Thanksgiving. They don’t care. They still have to be taken care of – and farmers understand that.”

Economic Mainstay

With direct employment of 28,500 people, the chicken and egg industry has a total impact on Mississippi’s economy of $20 billion, according to the National Chicken Council and the U.S. Poultry and Egg Association. That same report estimates the industry pays $1.5 billion in federal, state and local taxes. In addition to the 1,700 family-run poultry farms around the state, Mississippi has 50 processing plants, hatcheries, feed mills and egg farms. These businesses interact with banks, real estate firms, insurance agencies, farm supply stores, grain farmers, plant and poultry house equipment manufacturers who are allied members of the association.

-Mississippi Poultry Association